With this post, I am starting a series of “what were the schools like” in the Soviet Union, mostly for my grandchildren’s benefit.

***

Schools in the Soviet Union used to be way more uniform than in the United States. That’s why, although I describe the schools I attended, most things were the same no matter where in the Soviet Union the school was. The situation started to change rapidly during Perestroika, but until then, things remained remarkably unchanged.

Though the title of this post says “Elementary,” the concept of “elementary” was rather abstract. Except for rural areas and some specialized schools, a school would host all grades from first to tenth, and unless somebody moved (which didn’t often happen in the Soviet Union), you would be together with the same thirty classmates for five to six hours a day six days a week for ten years!

The majority of schools were what is called “zoned” schools in the US, meaning that you have to live within certain boundaries from the school to be able to attend it, and most times, there was no choice.

My situation was slightly different because the school nearest to me was a “specialized school with in-depth learning of English.”

This fact created an interesting disposition because the school had to take all the kids who lived nearby, but also, somehow, the kids who lived further away could get in through an interview. After Perestroika, the entrance exams to elementary school became common, but in the Soviet Union, these were uncommon and, if I get it right, sort of “unofficial.”

Unfortunately, my mom is not a source of reliable information anymore, and she can’t tell how exactly it worked. I remember she took me to an interview several months before school started, and I know she was anxious that they might not take me because I could not pronounce the “r” sound.

I do not remember the questions the interviewing commission asked me, but it was an easy conversation. Once again, I can’t tell why I had to go through the interview. There were several kids from “troubled families” in my class and some from “working-class families” whose parents were unlikely to care about what school their kids were attending.

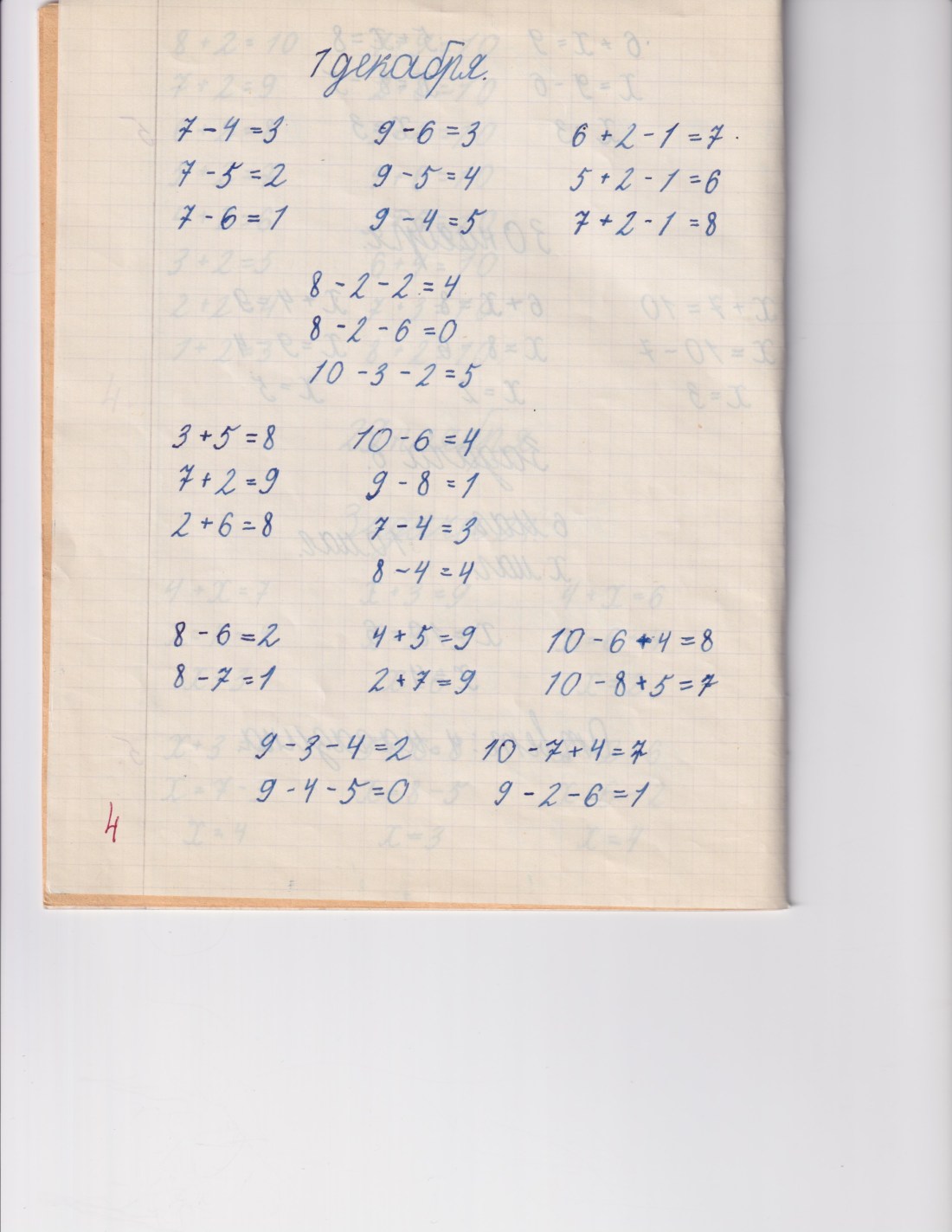

In the first grade, our curriculum was identical to that of all the first grades n the Soviet Union. We attended school six days a week, and we had four periods each day. Three periods were always the same, reading, writing, and math. And for the fourth period, we had PE twice a week, “labor” (that weird subject included anything done “by hands” mostly crafts; do not ask me why “labor”), art (drawing) once a week, and music (singing) once a week. The order of periods differed each day: all three core subjects were taught by our room teacher, and different teachers taught the other three, so we had to fit into their schedules.

The classes started at 9 AM. Each period was 45 minutes, and the breaks were either ten or twenty minutes (“long breaks”). One of the long breaks was a lunch break. For the first graders, it was from 10-40 to 11 AM. While in elementary school, we didn’t have the option to choose what to have for lunch, and as far as I remember, we didn’t have an option NOT to have lunch. At the same time, lunches were not free. Each of us had to bring one ruble on Monday that covered that week’s lunches. Our teacher would call each of us to her desk in the morning, and each of us had to come up and give her that one ruble, and she would make a note in her list. I remember that once, a student gave her a ruble torn into two pieces, and I remember her yelling at him.

It was always a hot lunch, but the quality of it was relatively poor, as with almost all of the “public catering” in the Soviet Union. Surprisingly to Americans, milk was not a part of that lunch. Middle-schoolers had an option of buying their snack, which included milk and pastry, and we all could not wait for this option to become available. We barely ate this lunch; we would all go home at 1 PM and eat lunch there, so it’s not like it was so necessary.

The school was less than ten minute’s walk from my house, but I had to cross the street (not at the intersection), so my mom was very anxious about it. I even remember how she taught me to ask “an adult” to help me to cross. The short way to get to my school was through the passage yard, and the entrance was almost in front of our building; that’s why I was crossing not at the intersection. To be honest, there was no significant difference since the rules of the road were loosely obeyed by all parties.

My historical posts are being published in random order. Please refer to the page Hettie’s timeline to find where exactly each post belongs and what was before and after.