Another thing which has happened that spring was my atopic pregnancy, which was just short of ending tragically. I refused to go to the hospital even after I’ve collapsed on the kitchen floor, and my mom called 03. Fortunately, the doctor told me: we will take one more call, and then I’ll come back. By the time they were back, I was ready:).

There was a reason I refused to go: nobody except me has ever taken care of Vlad and Anna. Except for Boris for a couple of hours here and there. I remember half-lying down on my mother’s bed (no idea, why on her’s, not mine) and dictating each and the single thing about the babies: sleep times, meal times, amount of food, naps, clothes for inside and outdoors. I remember that Boris managed to come before I was taken to the hospital, although I do not understand how he could get there on time.

I didn’t know what was going on with me, except that I could not move and could not breathe. When the doctor in the hospital has told me I have an atopic pregnancy, I didn’t believe her. I was taken to the operating room right away, and I remember that the surgeon asked me whether I want another tube to be removed as well. It’s hard to believe, but just a week before that Boris and I were talking about that option, and he said that he does not like the idea of doing something non-revertable. So I said no.

After the surgery, I’ve stayed in the hospital for five more days; eight patients in the room, atopic pregnancies, abortions, ovarian cancer – you name it, ages from nineteen to seventy-five. Two hours a day for visitors.

I had no breast milk the first day, and I thought it’s gone for good, but the next day it has reappeared. I’ve started to pump, just for the sake of keeping it coming, and it was then that I saw it was yellowish-grey and half transparent. To the” breastfeeding only” fanatics: I am absolutely sure my babies were better off with the US baby formula (that’s when it became handy, the Christmas gift from a Jewish charity!). After five days, my stitches were removed, and I was allowed to go home the next morning. I left the same night.

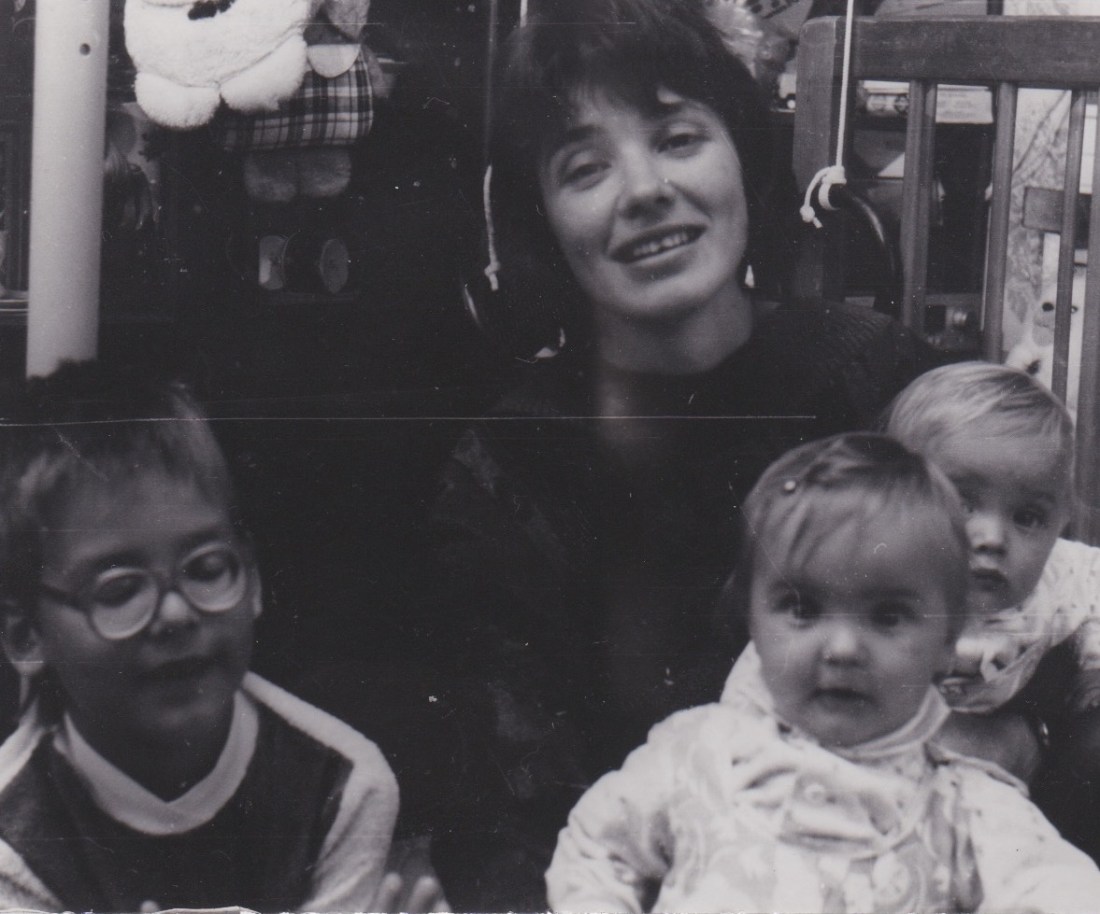

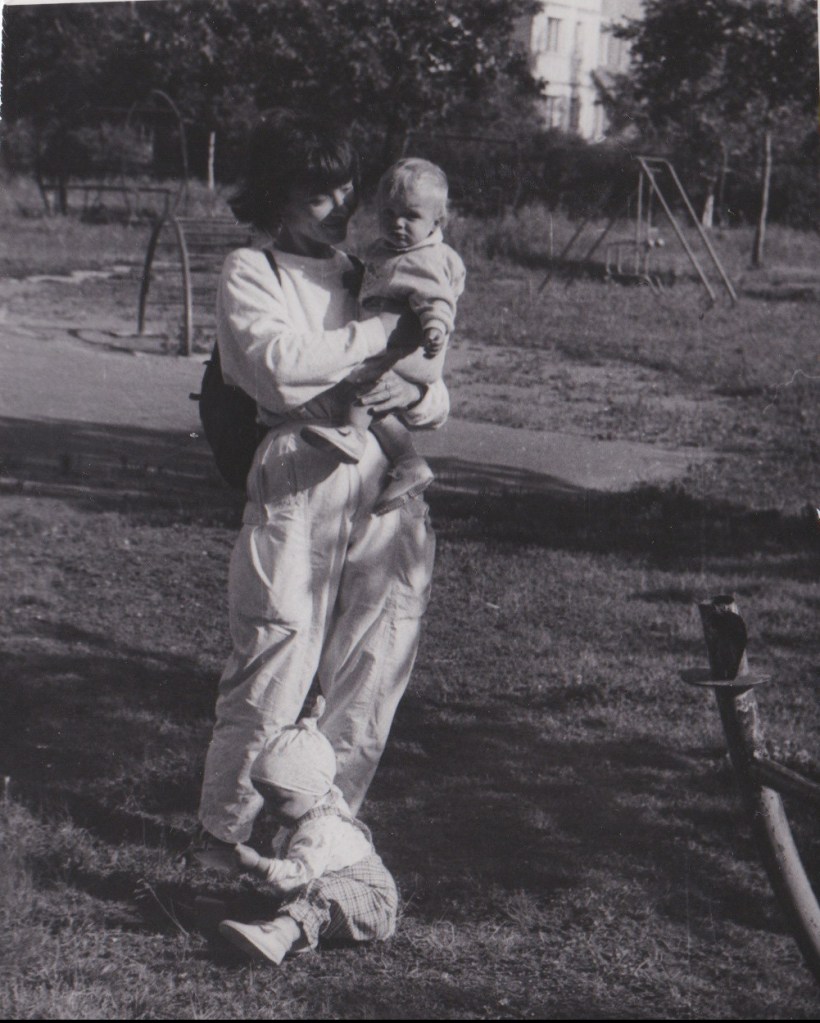

I was not allowed to lift any significant weight after the surgery, so I had to crowdsource my childcare. All of my friends who could come, for half a day, or for just an hour, were coming when they could. When nobody was around, I was moving on my knees and lifting the babies from that position.

Still, the warmer weather was approaching, at least theoretically, and life was turning for the better. By June, I’ve returned back to work at the University. This didn’t change much in my life since the year was 1992, and the people, whos’ salaries were financed by the government, didn’t get paid for months.

But fortunately, there was another perk. A relict from the Soviet times, when the local Unions were another branch of government – a summer boarding house.

I need to step back and explain what was so special about this last fact. I haven’t met with this perception in the States, but I might have a wrong referential group. In the Soviet Union and later in Russia there was no concept of suburbs in the American sense. We lived in the cities with relatively high pollution level. Granted there were magnitude fewer cars on the streets, but their engines were producing a lot of pollution. Besides, there were plants and factories, and there were not enough parks.

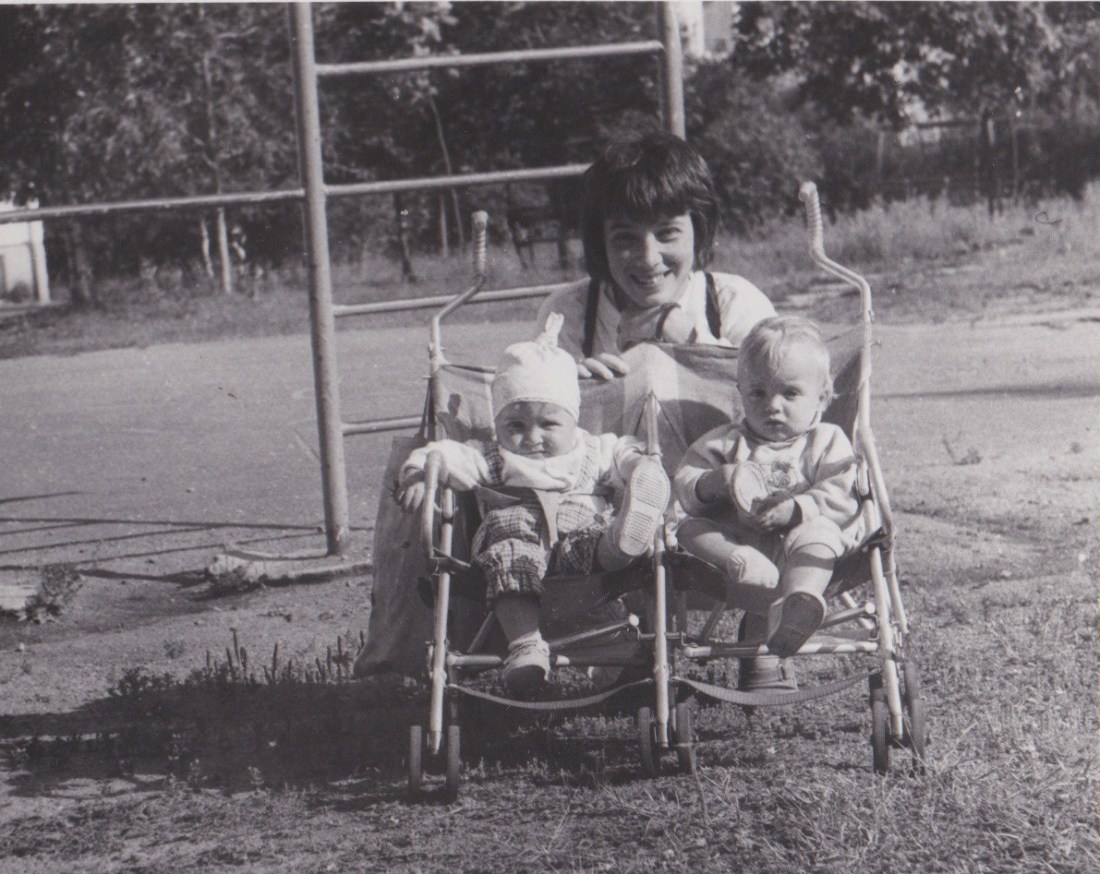

Any good mother had to provide a way for her children to “get some fresh air” during summer. This meant ideally to find a dacha somewhere in the countryside, where the children could stay with rotating parents/grandparents or send her children to the pioneer camp. The camp was for the children who were already in grade school, meaning they should have been seven or older. The younger children could be sent to a dacha with their daycare, but by my time, very few of them had dachas.

Besides each mother would have to resolve a dilemma, which way she would be the worst mother: if she would send her child to the daycare dacha, where she should suffer without her mother, or if she would have her stay in a polluted city and attend a “daycare on duty.” Many daycare facilities would close for summer without providing any alternatives. So you would be labeled a bad mother in any case :).

The University boarding house was a relict from the Soviet Union epoch and a present from heaven for me. It was opened all year long, but the summer sessions were in particular demand.

The University of Saint-Petersburg STEM campus was located outside of the city, in the countryside, or rather in the middle of nowhere. That was an idea of academician Alexandrov to build a university campus “as they do on the West.” There were many things wrong with this idea in the Soviet Union times, but a side effect was this boarding house right there, clean air, very little of civilization, and almost across the street of my work.

The price for the 3-weeks stay was pretty symbolic, especially counting the fact that we were getting meals three times a day, and most of the time they were eatable. I did buy extra fruits and other stuff for the kids, but that was fine. In the boarding house, I had more space than in my apartment, I barely ever had to cook and wash the dishes. I slept for 7 hours straight and was having a real vacation. Whatever work had to be done, was done primarily when Vlad and Anna were asleep.