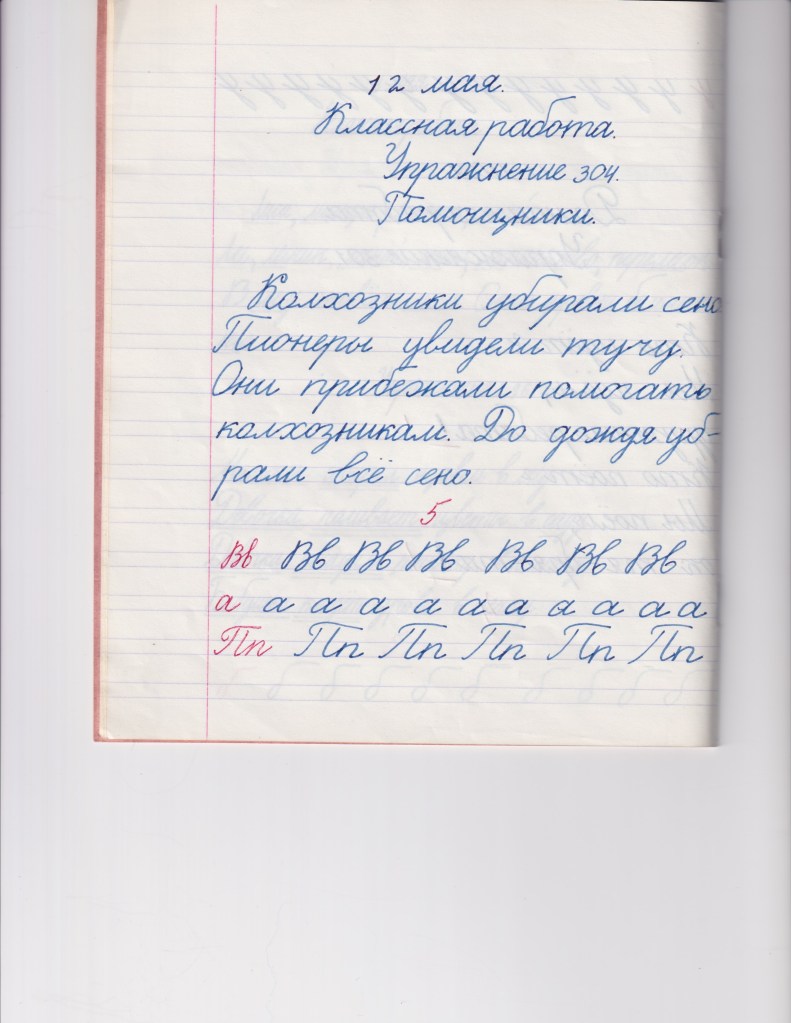

I plan to write a series of blog posts about school, similar to the series I wrote about the university. I do not have as many pictures from my school years as I would need to illustrate everything I am going to write about, but I have a lot of my school notebooks saved by my mom.

I have two of my very first notebooks in storage, and I will scan them at some point in the future, but I didn’t want to wait until this future came, so here are several others.

All of them are from my first grade. There was no Kindergarten class at school, and I already described our Kindergarten education when I blogged about my detsky sad. What I started in September 1970 was a first grade; whatever was before was not considered school.

Our notebooks were not at all like nowadays notebooks. The cover was made of thin paper, ad there were only twelve pages in each, We had six notebooks circulating at any given time: two for the Russian language, two for math, and two for penmanship. At the beginning of the lesson, you would turn in your notebook with your homework and pick up your other notebook with your yesterday’s homework graded by your teacher. You would do your classwork in that notebook, then do the homework in the same notebook, and the process would be repeated the next moring.